HOMEPAGE

|

Their children: Their children: Their children: Their children: Their children:

Their children: (Emma's dad was Francis (1825-?) married to Hannah Parnell (1821-?). Thomas, the father of Francis was married to Ann Young. Hannah's father was Thomas (1794-) and her mother (also) Ann Young (1793-?) Their children: Edward Harry (1884-1971), Annie Louisa (1886-1949), William John Newman (1888-?), Amelia Minnie Georgina (1891-1939), Bertie (1893-1958), Daisy Lillian (1896-1966), Ernest A. (1898-1917), John (1900-?), Louise Ellen (1902-1981), Walter Sidney (1905-1991) Frances Ethel's father was Charles Clark (1856-1934, her mother Eleanor King (1861-1919). Her grandfather was Charles Clark (1815-?) and her grandmother Elizabeth Fugett (1821-1899). Elizabeth's parents were, father John (1794-?) mother, Sarah Paul (1789-?) Eleanor King's father was Simon King (1835-1887), Henry King (1793-1879 was her grandfather, and her grandmother was Jane Douglass Oliver (1773-1869)) Their children: John Walter Francis (1935-?), Jean Ann (1938-?) Ivan Charles (1940-?) Their children: Elizabeth Maureen (1958-?), Stephen John (1959-?), Patricia Jean (1965-?), Sarah Frances (1967-?) |

|

Cheriton was a small village, perhaps just big enough to support John in his tailoring business. John and Ann had seven children, and their first child died under the age of one year. There are nine generations going back from my Dad, Walter Sidney to John of 1643. In that nine generations there are two Johns, three Williams, one Henry, two Harrys one Walter. These Dads shared a variety of surnames: Titheridge, Tytheridge, Tethreg, Tythereg. These are by no means the last of the names ascribed to the family. These discrepancies are blamed on the fact many people could not read or write: When asked their surnames, the official [who could read and write] would have to guess the spelling. In some cases there are different spellings within the same family.

Included here is a link generated by Ann Titheradge [yes!] who at the time of writing [October 2021] was the acknowledged family expert. https://titheradgefamilyhistory.wordpress.com/photographs-of-cheriton-hampshire/ Her web site can be found at: https://www.Facebook.com/groups/titheradgegenealogy/

JOHN'S GRAND PARENTS CLARK AND TIDRIDGE

Summary: There are nine generations between John W. F. and John Titheridge our first known ancestor. John was a tailor. It is likely other ancestors were agricultural workers; some skilled, others labourers.Titheridge was a cabinet maker. He was the first known Tidridge, Harry and Harry J were head gardeners. The families were large: average size from John Titheridge to John T's grandfather, 8.38 children. There were four families of ten or more. Six of the families lost a child in the first year. It would seem that apart from John Titheridge most of our ancestors followed employment on the land. Summary: There are nine generations between John W. F. and John Titheridge our first known ancestor. John was a tailor. It is likely other ancestors were agricultural workers; some skilled, others labourers. Henry Titheridge was a cabinet maker. He was the first known Tidridge, Harry and Harry J were head gardeners. The families were large: average size from John Titheridge to John T's grandfather, 8.38 children. There were four families of ten or more. Six of the families lost a child in the first year. It would seem that apart from John Titheridge most of our ancestors followed employment on the land. . This changed somewhat with my grandfather’s family. The family moved from Bishop’s Waltham, to Southampton. His oldest son [Edward] immigrated to the States and was in business, his sister, also moved to the States. Louise was a stay at home mother, brother Bert was in Real Estate, Will was owner his own store. Brother George was a grounds keeper, his sister Daisy looked after her parents, Ernie died in WWI, John died at less that a year old, Louise, not sure probably a stay at home mother, and Minnie...the black sheep of the family. And finally Sid, my Dad, started off with the post office, then went to sea as a steward...left just before the war and had a multitude of semi-skilled jobs. He was an excellent provider. A link that might be found interesting: https://tidridge.github.io/TIDRIDGE_NEWMAN_Harry_John_63.htm

TIDRIDGE GRAND PARENTS

I remember about as much about Grandfather Tidridge as I do granny!! He died in 1941 when I would have been about six years old. I have this picture in my mind of him coming down Silverdale Road where he lived, very slowly, using a cane. He had beard. I recall he gave me a penny. Granddad was a gardener, church worker, and a sportsman of some repute. He was also heavily involved in the Southampton Football (soccer) Team, being the man collecting the money at the entrance gate for many years: He was also a champion lawn bowler, and was connected with the Hampshire County Cricket team as an umpire. He was important enough that the Mayor and his wife came to his and granny's wedding anniversary!

The Tidridge home was located on Silverdale Rd, #2 I believe. I do not know whether they owned the house or not. It was a terrace home, on a pleasant street. I remember that you had to go up steps to the front door: The wall outside the door was of tile and there was a picture of a man with a gun, a sort of hunting scene.

The house seemed to stretch way back, there were at least two rooms on the right hand side of the passage way, with the stairs facing you. I do not recall ever going up the stairs, but I think there were three floors. The passageway finished at the dining room and then, continuing through the dining room, you reached the kitchen. There was a small, immaculately kept back yard. The back gate led into an alley. I always remembered the entire house being dark and gloomy... sort of matched the Tidridge personality.

There were, I think, eleven little Tidridges'. A couple left for the United States where they raised large families. It would appear some turned to the Roman Catholic Church. Apparently this caused some unhappiness. At least one of the children became a minister in the Protestant faith. I met one of the American cousins during the war when he came over as a soldier.

CLARK GRAND PARENTS AND FAMILY

As I have stated elsewhere Hedge End figured prominently in my childhood!! We had many aunts and uncles in the area. One of Mum's brother's, four of her sisters remained in Hedge End! They all seemed to produce lots of children so I had scores of cousins. All older than me; Mum was the youngest in her family.

The Clark family: L to R top row:Amy, husband Jim. Next row: Ada, husband Alf Farmer, lived at Lockerly, Hants, Elsie Harding, lost her husband in WW I, Grandma Clark, Charlie died in WW I. next row: Lily wife to Harry Goodall, operated Hillsbrow Stores, Bursledon Rd. Hedge, Hants, Martha wife to Wally Gadsby, lived just down the road from the Goodalls. next row: Ernie lived on Heath House Lane just a few steps from the Barfoots.

Charles and Eleanor (nee King), were Market Gardeners with their own accounts and by 1911, the family are living in “Harefield”, Bursledon Road. Charles and Eleanor had worked at Harefield Farm and subsequently chose this name for their home in Hedge End..

Left Charlie and his fiance. He was killed in WW

Right..Grandad Clark with, possibly Ethel Frances

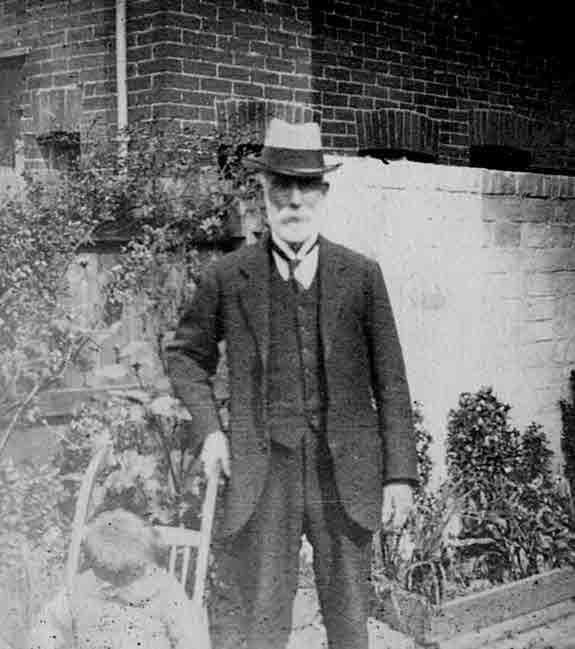

Granddad Tidridge; You will notice the three piece suit, collar and tie. I read somewhere this was the standard working uniform for all workers. The bottom button of the waistcoat was left open to permit freer movement.

Hedge End War Memorial. Contains Charlie's name. Photo provided by Town Clerk.

WALTER SIDNEY TIDRIDGE [[1905-1990] Walter Sidney (Sid) Tidridge (1905-1990) was my Dad, he was the youngest of a large family", and was born in Southampton, Hampshire, England. I know little of his younger years except that he attended Western School, Southampton. Played soccer, was left footed. On leaving school he began to work at the Post Office. He was dissatisfied with either the rate of promotion or the possibility of promotion and joined the Merchant Navy. He was a steward. A steward is a person who is, to all intents and purposes, a servant who makes beds, cleans the rooms (cabins) and tries to make the sea trip for the passenger as comfortable as possible: This career most likely accounts Dad's habit of grabbing a duster when he came home and perfecting what Mum had already done in the way of housework. It would seem reasonable to believe that this did not do much for Dad's popularity!! I believe that Dad's career took him to France, South Africa, South and North America, and possibly Germany. I do not recall too much about his trips but he did talk of "crossing the line”, Dad left he service under mysterious circumstances just before the beginning of World War II. I was led to understand he had been fired, but I never did find out why!! He would have been around thirty years of age. He served on the ship called the Asturias. Dad never did any military service. I think he did not meet the medical requirements as he had severe ulcers on both his legs. The cause of the ulcers was attributed to several unproven happenings. One, the fact that as a telegraph boy he wore 'puttees' and the bindings apparently caused constriction of the blood and caused the ulcers, or two, the many years he served as a steward on carpeted floors seriously Dad seemed to have a variety of jobs, mostly semi-skilled. I recall that he was a riveter's helper, a warehouse man and lastly a stevedore. As a riveter's helper he assisted in the building of spitfires, so successful against the Germans in WW II You have of course, checked the Family Tree so carefully prepared. A ceremony held on board ship when the Equator was crossed. King Neptune, King of the sea would come on board and then some age-old ceremony occurred. This involved soap shaving and dunking in a pool. Or so I have been told. He was an Air Raid Warden during the war: this was an organization that helped during the bombing. In those days a telegram was sent and delivered by a telegraph person, who delivered it to the home of the addressee. For you landlocked Albertans this is a person who unloads ships.

FRANCES ETHEL TIDRIDGE nee CLARK

Her parents were not rich, but I think they did own some land they worked and lived on. I was born in a house belonging to them, Harefield House. The house was still standing when we visited in the late 1980's. I think Mum must have lived there when she and Dad were first married. You'll remember my Dad was at sea (not all at, but serving at). Mum and Dad either bought or were given as a wedding present a house in Hedge End. The house was still standing in 1991. Mum and Dad sold it to a family member, Ray Gadsby, and you all received a little of the proceeds. Aunty Edie and Uncle Ern lived in the house for years. You won't remember them, but you met them in 1961 and 1971. Sarah, you won't remember, but you took to Uncle Em, would have nothing to do with my Dad. It didn't go over too well. You would have all liked Uncle Em he was, in my view, the epitome of what the middle class Englishman should be, polite, cheerful, honest to a fault, a fine gentleman. So you can see you come from a long line of rich property owners, ho! ho! ho! I do believe, though, it is that sort of back-ground that decides your course of action throughout life. In this case my grandparents were homeowners, so were my parents, and consequently that was your Mum’s and my objective: to own a home. I'm a sure Mum's parents were the same. Some more on my Mum in service: the person she worked for was I, think, a Judge, and fancy dinners were held and the whole bit. OK for the host and family but a bit of a bind for the hired help. I think Mum worked for some real 'twerps', i.e., head cooks and butlers who were a bit of a bother to work for. Mum, because she was around most of the time, handled the discipline. She was quite 'handy' and 'a clip around the ear', especially if her wedding ring contacted your head, really got your attention. It made quite an impression. No pun intended. I remember when someone became too big (no names here) a small, wand like cane, was purchased. It meant Mum could reach further. I distinctly remember her chasing me down the garden path, cane in hand, making contact on at least a couple of occasions. The heinous crime has long been forgotten. The cane was 'accidentally' destroyed in a boisterous moment by yours truly and never replaced. The reason being I became perfect at a very early age! Mum was kind and considerate. (February 20, 1993) Sometimes as we grow older our attitudes change and I guess parents can be a real pain. Aunt Jean wrote Mum developed into a bit of a nag: Jean, John and Dad being the recipients of most of her 'concerns'. I never knew her as anything but kind and considerate. I think Jean had some problems to resolve when Mum died. I'm glad to say, however, a couple of years Jean has kinder memories. Mum used to visit various little old ladies; you just didn't hop into a car and take off, it meant a trip by bus. So in effect, you just didn't drop in on a person. It made a day long trip away from home. (February 20, 1993) We take everything for granted in Canada, although I fear with the economic position of this province and the country, things may get worse before they get better. Some things we take for granted may just not be b available. (September 9, 1998) The economy returned to normal but not before many people lost their jobs. It was the era of down sizing. Fortunately, the down sizing did not adversely affect this family. On occasion, when Mum was away, she would pack lunch for me. I would eat it, at the home a Mrs. Smallwood, probably a widow. She lived in a small house some distance away. She had two pictures that I remember; one was called The Wreck of the Hesperus. You will all remember at times being told you looked like, The Wreck of the Hesperus. Just to fill you in a little, as if you cared! As I recall the ship ran aground or sank not too far from shore, unfortunately the waters were filled with sharks, you can guess the rest. The other, a battle scene: It showed troops all lined up to do battle. Real cheery pictures to eat lunch by! Mrs. Smallwood, a member of the Women's Voluntary Service, sold savings stamps to help the war effort. That won't mean anything to you, but I stuck it in because that what she was and did! Savings stamps were sold to people during the Second WorId War; the monies helped the war effort. Mum, along with Dad, was also a cleanliness freak. No wonder I exhibited traits of God-liness! Necks, ears, behind the ears, fingernails all had to be cleaner than the original! Our clothes were always clean and repaired. A constant chore as far as I was concerned, I never was careful with my clothes. Underwear always had to be clean and in good repair, just in case you got into an accident. Funny, funny, funneeee! I suppose you all know I was Mum's favourite: She picked out all of my clothes until I went in the Army at 18. She even picked my Wedding suit for me, after I came out of the Army! Your Mum was probably surprised she let me come to Canada: Just kidding. (February 20, 1993) I bet you all got a kick out of the last sentence. I never felt it strange that my Mother held such a firm grip on my life. She would probably have wanted to have selected, rather than approved of, my selection of the girl who was to become your mother! I suppose on looking back, my parents ran my life for me. I don't think they saw anything wrong with it. Money was tight; Mother knew best, I had no argument with the setup. I really believe that they were doing what they felt was best for all of us kids. I know you probably think you were kept in check; what with pants with maple leaves on them. You know what your Mum and I really thought? We were trying to bring you all up to be independent. We think we did a good job. I have never, because of my family upbringing, found it too hard to follow rules or fit into a rules-oriented occupation: For example, the army or the police service. That made life in both organizations much easier. Even now, some 40 odd years later I have no problem following most regulations. I enjoy trying to change some of them though. Never felt myself as the pet of the family, some pet! Never went through the rebellion stage, at least, I don't think I did. I was too busy working and playing sport. My Mum used some weird expressions, such as, 'you look as though you have been dragged through a hedge backwards': 'Excuse me miss, your hair's a-twist, your petticoat shows your garter miss', and one that says it all ' you're as useless as tits on a boar'. The last remark probably used in desperation rather than normal everyday chatter! And, in a moment of weakness, taught us, 'polish it behind the door', which if repeated quickly will get you into trouble! Mum was not athletically inclined, but she did join in the odd game of cricket. No smart remarks about cricket being odd, and soccer, and would try the game of rounders, the original version of baseball She was always stiff the next day. Sex was never discussed around the house, unless in the context that it was the number after five. Mum did give me a book on the 'birds and the bees' when I was around 12-13 years of age. I was pitifully ignorant on the subject. However, when I consider today's 'educated values' I'm not sure which was better or worse. I do remember Mum saying she thought that sexual intercourse was intended for a husband and wife. I have never had any problem with that idea. During the war when most things were scarce, we seemed to do well. My Mum kept chickens, for eggs and meat, and rabbits for fun and meat (sorry Trish and Sarah) Mum, as I have mentioned was from a farm background. My Dad was NOT. Mum didn't smoke, thought it to be un-lady like. She tried it, I believe, but didn't dig it. Other ladies smoking did not bother her, but thought that it should be done in the house and not the street. I'm not sure where Mum was from a religious point of view. She believed in God, read her bible regularly, and probably said her prayers. I do not recall her sharing her faith with me. She was very much behind our attending church and Sunday School. She must have talked about her childhood but I forget much of what she said. I had written to her in 1986 for more information. I'm still waiting for her reply. As for schooling, I do remember, both Dad and Uncle Em kidding Mum and Auntie Edie about their attendance at Hedge End University, the village school. Mum had started left-handed but that was against the rules in those days, and she was forced to become right-handed. My Mum's pride was her garden: she was very good at it. She seemed to know a great deal about plants, how to garden. Our garden was always one of the best in the road. As I write this, April 24, 1991, Mum is 83 years old. She is not enjoying the best of health. In the last little while she has had operations on her eyes for cataracts, which, according to my sister Jean's last letter, were unsuccessful. While in hospital she fell out of bed and broke a hip. She is also becoming deaf. Mum is missing Dad, though they were not particularly happy in their later years. She is living in a good hotel/lodge for seniors and is well looked after. Jean and John visit regularly. I would rate her to be the best Mum's I have known! February 2017:John corresponded with his sister to get more information on Mum's earlier life. It was pretty sketchy. Starting work at 14, at Lockerly, mum apparently cycled home for the weekends a distance of some 20 miles or 32 kms. At some time she worked at Sway and became friends with Rene and Henry, where Maureen and I spent part of our honeymoon. Mum was a housemaid.It was at Sway where she met her future husband. Dad had been on a charabanc ride. But that's all we know. [It stretches the mind to see why anyone would take a ride to Sway] I have it stuck in his mind that Mum also worked in a judge's home [Bayford] but cannot confirm this. The judge lived within walking distance of Hedge End. Jean related the couple were planning to buy a home in Pretoria Rd. Hedge End, Dad had sent money home while he was at sea but learned his mother had spent it all. This meant that Mum's Dad would not allow Dad's name to be put on the deed. A bone of contention indeed. The house, which they kept after they moved to Totton, was [said to be a financial drain] a financial drain. There was also Auntie Mabs living them for many years... I imagine this was a trial of patience, understanding and a lots of other things. Oh, yes and we three kids! I understand from my sister Jean she had some problems with her two sons heading off to seek their fortunes. If this was a concern it was not reflected in the way she kept in contact through frequent letters. I concede Mum had the longest apron strings in the world and it took many years to really be freed of this... but then being the favourite son... ha!

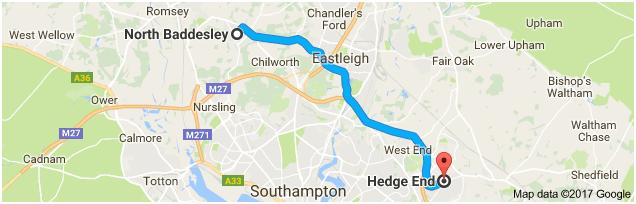

The map shows the portion of Hampshire where the C larks/Tidridges lived....not all places are named but travel between the places was by bus, with many stops along the way....it must have been a huge waste of time but I imagine modern, increase in traffic has not shortened the travel time by very much..

Ethel and Sis's Wedding party. The event was reported in the Southern Daily Echo, the still published news-paper.

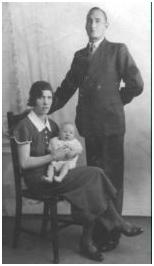

[It looks as though the wedding was a big affair as all the weddings were for those connected to Hedge End and families. John and Maureen broke the mould. They were leaving for Canada and a big wedding was not in the cards. It was held at a small Baptist Church in Thornhill, and the reception in the home of a friend of the Barretts. Methinks my Dad found the Hedge End connections pretty intimidating at times! Mum and Dad lived in Hedge End for a period after they were first married.] The Tidridges moved to Pretoria Rd. still in Hedge End, and Dad remained at sea, leaving just before the war started in 1939. What can John Tidridge say, other than the pride and joy of the Tidridge family arrived! The year would have been 1935. The family moved to Totton when John was 18 months old, and there were no other children at this point. Jean arrived in 1938, Ivan in 1940.

Perhaps

they are still showing old English films. The class system in the servant class was bad, if not worse than the one in the ruling class.. Butwe only had one bath a week. Churchof England [Anglican]

MAUREEN TIDRIDGE nee BARRETT I first met Maureen in 1955 when I came home from leave in Germany. But, here is a story of how we met. I was stationed in barracks [Hubbelrath] on the outskirts of Düsseldorf, it was a large settlement and included a Rest and Relaxation centre where food was available. There was an area [I think] that must have provided room to sit and read magazines. I picked up a movie magazine and found there was a section where people could start a pen-pal relationship. Nothing appealed to me on my first reading. The next week an item the caught my eye: A young lady living in Thornhill, Hampshire, some 10 miles [16 km] from where I lived and would be for the duration of my leave. I wrote she wrote, we wrote some more and some more and finally we met in the fall of 1955.

I travelled by bus from Totton to Thornhill...Maureen was waiting at the bus stop...and the rest is, as they say, history. We married in February 1957, are still married in 2021. Our family has grown somewhat. Our children are Elizabeth, [Tuppy] Steve, [Michelle] Trish [Ted] and Sarah [Ken]. Stephanie, [David] Rachael, [Keith] Andrea, [Danion] Sarah, [Colin] Isaac, [Kathryn] Trevor, [Nicole] Megan, [Mark] David, Emily [Justin] and Koen are our grandchildren. Felicity, Reuben, Jude and Sullivan and Gwen are the great grandchildren.

Maureen, bless her heart, is not into displays or unauthorized stories about her! However, the URL following will show the family over several years. https://tidridge.github.io/BARRETT_Family.htm

MAUREEN BARRETT Like me she comes from a middle class family, although she is sure the railway tracks moved for me. She was a go good student. This is a picture of her class at Wildern Lane School, West End, Hampshire. She participated in school activities such as musicals etc. An excellent student who took a business course toward the end of her schooling. Maureen worked as as a clerk with a Builders Supply firm. Very good at it too.

Mum and Dad Barrett treated me as a son [probably recognized my high qualities as a future son-in-law]. They were just good people. They are, in fact, responsible for you children and your descendants being Canadian! It’s too long a story too write it all but the basics are as follows: I had been recalled to the army because of the Suez Crisis. Your mother took in a travelogue about Canada. She told her family, and in short order it was, “Look out Canada, here we come”. I learned all about this when I collected my mail delayed while I visited Egypt, Malta and Cyprus. And, to cap it all, your mother was off to Canada... and this is where she would have gone, without me, except for some pretty nifty work by family and government officials. Oh, yes, and we managed to get married while all this was going on... this all occurred in February 1957. Maureen has two sisters and two brothers. A fine bunch indeed. They have produced several offspring. Although the whole family came to Canada, everyone except your mother and I, returned to England. We have no regrets.

Maureen did an admirable job raising the family! And me!

Maureen and her siblings, left to right Pat, Michael, Maureen, Kevin, Christine

SIBLINGS SISTER JEAN Jean Ann Tidridge, my sister, your aunt, was born March 4, 1938. When I started this in 1999 I could not remember too much about Jean. That should not be construed as being negative! I recall she was very sick at times with asthma. She spent some time at Hedge End, because it was at a higher level, topographically speaking. She was obviously smarter than me, as she finished up at a grammar school, Brockenhurst. Jean trained to be a telephone operator. She married John Bathgate, an executive with the Telephone Company. Jean visited here with my Mum. She returned with her husband many years later. John and Michael are her sons. Jean and John were the caregivers for Mum and Dad in their latter years. This meant lots of travel and a goodly amount of their time being given to this task. I think it took its toll. I have always, as far as I know, got along well with Jean. When we visited in 2000 we stayed with Jean and John and they treated us very well. BROTHER IVAN Ivan Charles Tidridge, my brother, your Uncle, was born August 19, 1940. The battle of Britain was raging when he was born. There is no Russian in my brother. Ivan, the name of a person who was, I think a Godfather, Ivan Elton. Don't ask anymore, I don't know any more!! November 27, 1999. Again, I remember very little at this time about Ivan. He was, I believe, more outgoing than me, and rather fancied himself as a ladies man! He also went to Brockenhurst Grammar School. He served his apprenticeship as a carpenter. Then he joined the police service, for the County of Hampshire. He and his wife, Phyl, later headed off to Australia. Alec and Sandra are their children. Like me, he missed out on having to look after Mum and Dad. It has been almost thirty years since I saw him last. We write occasionally, exchange phone calls with Ivan always managing to call (very) early in the morning. At the present time we hoping travel back to Jolly Olde and all meet up again. I don't think we ever had any disagreements, although he was of the opinion that I was number one son with my Mum!! I can't think why!! June 30, 2002: We, Mum and I, had travelled to England in 2000. Met with Ivan and his wife Phyl there; apparently he was under the impression I had said I was better than him because I was a Christian. Can't think how that happened: Don't even remember talking to him about Christian things. However, to cut a long story short, we are now the best of brothers and correspond regularly via e-mail. We played a game of golf in England, he beat me badly, but it was a very enjoyable day spent on the links. July 2003, still emailing Ivan, on a regular basis, both letters and a discussion on Christian things: The Christian discussion died out after half a dozen or so letters. Ivan was happy with what he believed, which was the normal understanding of a distant God and no need to get too personal.

THE FARM

Hedge End, Hampshire, played a large part in my early childhood, probably that's because Mum was born there and it was where most of her sisters lived. She was the youngest of a large family. Her sisters were Lil, Martha, Lizzie, Amy, Elsie Ada, and her brother was Ernie. She lost a brother, Charles, in the First World War. Our family visited Hedge End often.

I don't think that my Dad was too impressed. I'm sure it was a cause of disagreement between Mum and Dad. Many of my summers were spent with Uncle Fred and Aunty Liz on their farm. I think they rented the place, but that doesn't really matter. I have no idea how many acres the farm was in total. It was undoubtedly small by western Canadian standards. They did a little bit of everything. They grew strawberries, lettuce, carrots and wheat; Kept ducks, chicken, pigs and cows. A real mixed bag.

The farmhouse was old and seemed big compared to our house at Totton. Thatch [it’s funny, but I have since learned that the roof was not'’t of thatch] covered the roof. If you are interested, thatch consists of several layers of straw all running the same way held in place, by I think, hazel wood strips, which were doubled into ‘u’ shaped pieces and forced down into the straw. Straight strips of the same hazel wood ran parallel across the length of the roof. When the ‘u’’ strips were forced down into the thatch the strips held the straw in place. Thatching is a skilled but not a growing trade.

From the outside the house looked like any of thousands that appear on plates and postcards of English cottages.

HEATH HOUSE FARM Entering the front door you were faced by the stairs. To the left was the parlour, I only recall being there once, and I don't recall the situation except that Uncle Fred played the accordion and sang. To the right was a huge living room and as you entered you could see a huge fireplace in front of you and to the left. Directly as you entered the room and facing you was an Anderson Indoor Air Raid shelter. I remember this as being a table made of iron. It was intended that the family stayed underneath this to be protected in case the house was hit during a bombing raid. This was during the Second World War. I have tried to remember where I slept. It must have been upstairs. I do remember that I slept under the shelter at least once, slept under the shelter at least once, woke needing to visit the bathroom, being scared to go outside and, instead, urinating in a tea cup that was on the top of the shelter. As best as I can recall no one ever mentioned the incident. May be I was not the first to seek an alternative method to visiting the biffy after dark!

There was no electric light, so paraffin lamps were used, this gave a very gentle light, did not illuminate a very large area, but allowed good shadow making on the walls. I recall that the furnishings were simple and well used. A huge dining room table dominated the room. There were two pictures I remember, they were on the wall opposite the fireplace. Both pictures showed a sailor. In one he was returning from the sea, the other returning to it, well to his ship anyway. The caption read on the appropriate picture, 'Jack's the Boy for Work', and, 'Jack's the Boy for Play'. Neither picture was in colour. I can remember no other pictures in the room. One other piece of furniture comes to mind, the bureau, a writing desk with shelves, with a draw out leaf, and drawers. I don't remember exactly where it was in the room but it had all kinds of papers in it. On top of it was teacup that had small change (pennies and halfpennies) from the milk run in it.

The way into the kitchen was via a doorway on the other end of the wall from where one had entered the living room. I remember the kitchen as being huge, having a paved, uneven floor. In one comer were two buckets of water. A daily chore I occasionally had was to fill these from the pump. A table was against the left hand wall. Above the table was a picture showing dozens of different roosters and chickens. A butter maker was also in the kitchen somewhere! It was a machine that had to be turned by hand and after much labour, butter was produced. Eggs, chicken and/or duck, were invariably on the table. Uncle Fred also kept two double-barrelled shotguns in the kitchen. They were in the comer in the far left hand side of the room. A window, above a waterless sink, looked out over the kitchen garden. The window was to the right as you entered the kitchen. The back door was on the right as well, between the window and the entry from the living room. I have little no recollection of the upstairs of the house except that one window overlooked the side yard. This side of the house had the pear tree trained to it. You could reach the pears from the window. To me it seemed the farm was miles from anywhere. Of course in fact it wasn't, as we discovered when we visited in 1971. It appeared that most of the farmland around it had been built on. This is a sad loss of some good agricultural land. The farm was some distance from the hub of our Hedge End life that was Auntie Lil's grocery store. Having walked, I suppose a mile, from Auntie Lil's along paved roads, one then turned into a gravel lane. This led to the farm. And, while distances shrink when you revisit as an adult, it still seemed like a mile to the farm. When you reached the farm the lane continued down to the left of the farmhouse. The farm drive led up to the farmhouse. It was quite picturesque. Two iron gates accentuated the driveway. I think the gates were closed occasionally.(On the right as you approached the house, was a garden, with all kinds of flowers, backed by a trellis. During the summer this trellis was covered with rambling roses. There also a lawn, which started partway down the driveway. The trellis bordered both the lawn and garden.

I don't remember the sort of flowers grown. I do remember however, two huge flowering shrubs that attracted hundreds of moths and butterflies during the summer. A flower bed was also on the left hand side of the driveway, this ended halfway to the house. Just before the border ended and some 4-5' in, was the water pump. Beyond the end of the border and set back 6-8 ' were two buildings. One was the dairy where the milk was handled. Next to it, was a storage shed of some kind? I remember seeing bicycles stored there and the smell of paraffin.

The driveway became two paths just as it reached the front of the house. One branched to the left the other to the right. Using the pathway to the left it dropped sharply and there was a border to the left as you descended, made of rocks: To the right a border of shrubs and trees against the house. These shrubs and trees extended along the front of the house. As you reached the end of the house, following the path to the left of the front door, the path branched again. If you continued on it took you out of the garden to the lane used to reach the farm, and to a huge barn. A car (an MG) and a tractor were stored in the barn.

Turning the comer to the right you were confronted by the outdoor biffy. Even though I remember it being attached to the house, there was no water. Memories still exist of early morning and late night visits. Always making me wonder what might be lurking in or around the shrubs. As I recall, the whole area was laced over with trees. It was pretty gloomy, even in the daytime. Avoiding the biffy, the path way continued around the house and reaching another comer, the path branched again. If you kept to the left, following the path, you would come to the lane again. The other branch took you along the back of the house. It seems to me that as you moved around the back of the house the path branched again. The one to the left led out into the fields through the back garden. The other led along the back of the house, up over steps, and then continued on to the other side of the house. Here you could either go straight on or go along the side of the house. If one travelled along the path to the end of the house, one came to a fairly large open area. This I will cover later. However, if you followed the path around the house you could not help but notice the huge pear tree, mentioned earlier. By following the path you reached the end of the house again a branch in the path. One led to the left to the open area, the other if you turned right, along the front of the house. While I recall that the front garden was always very good, the back yard looked like a wilderness. I cannot really remember it being cultivated. It seemed to consist of a very high growth of stinging nettles. Uncle Fred would cut these once in a while to use as feed for his horses. He would cut the nettles with a scythe. A scythe is what you will see in pictures of Old Father Time. He carries one over his shoulder. The blade was about 2.5 feet long, curved, and kept very sharp all the time. It was sharpened with a cigar shaped piece of carborundum stone: Quite a lethal weapon in the wrong hands. I recall being told to stand back when it was being used. Uncle Fred was something of an expert; at least it looked that way when he used it. To operate the scythe, the blade, held parallel to the ground, was taken from slightly behind you to the front in a sweeping motion, keeping the blade still parallel to the ground, but with the tip of the blade pointed slightly up. Depending on the skill of the operator a fairly wide swathe could be cut. Several large fruit trees grew in the garden. I don't recall if any of the fruit was ever picked or not, but I vividly recall seeing lots of plums rotting in the grass and weeds, covered with by wasps and bees.

The open area that I mentioned earlier brings back fond memories. I don't remember whom I played with, but there was someone. I do remember the old vehicle rusting away under the trees. It had a van body, with a cab. In the cab the remains of a seat, a steering wheel, with controls of some sort. I drove that van thousands of miles. Another interesting feature of the area was the trees. They overhung the edge of the area that dropped off sharply some 4-6 feet. I spent hours in the trees climbing up and down, hanging and swinging from the branches.

I suppose because of my young age I had no specific chores, although getting the water was one, occasionally. This required using the water pump. It had to be primed. Priming is pouring in a small amount of water into the top of the pump, and then pumping like crazy until you sucked up the main flow. The skill in using a pump, in my view, was that you had to pump expertly/quickly enough to make sure there was an unbroken flow of water from the pump to the bucket. An even greater skill was getting the full buckets to the kitchen without spilling the water.

Getting the cows in from the fields was another chore I helped with. Very little skill was involved as the cows were usually waiting at the gate. They knew their own way back to the barn and which stall belonged to them. If you have a chance, get a cow to run for you. They cross their back legs, and when running present a very strange sight. That's how English cows do it, strange but true. As I said earlier, the cows knew which were their stalls and need needed no direction from humans. The milking came next, all by hand. Milk can be squirted with great accuracy and one was in danger of getting a milk shake, unasked for, if one stood around doing nothing. My milking experience was limited. I never did find a cooperative cow!

I supervised the ploughing. That is, I followed my Uncle or his son, Ernie, in the single furrow created by the single share plough. Later, when the horses were replaced with a tractor, I stood in the tractor. It was after a days ploughing with horses that I had what I felt was a narrow escape from injury. After the horses had been unhitched from the plough I was seated on one of them (Ginger). It was sent off in the direction of the barn with me on its back. The horse forgot about me, and, if I had not had ducked going under the barn door I would have been dead meat! I never developed into a farm boy, but at least my experience helped when we came to Canada and we started on the farm at Genesee.

There were several incidents, however, that will always remain with me. One, helping on the milk run, a one horse wagon, loaded with milk churns, was trudging up a slight incline. Then one of the tires (tyres) punctured, with a load bang, away goes the horse at top speed. You have to realize that driving this horse meant holding the reins and clicking occasionally just to let the horse know you were still there. The horse knew where to stop, and started when you got back into the cart. Fortunately there was no other traffic on the road, the horse was not naturally disposed to long distance races and the fun was over almost before it began. Thank goodness.

I remember eating cow cake; cylindrical shapes 1-1.5 inches long, dark brown, made as I learned later, of mostly bran and linseed oil. They tasted good, but oh, boy, what that does to the stomach!! It seems I made several rapid trips to the biffy for a couple of days.

During the Second World War, still on the farm and going to a concert, people singing, telling jokes and etc. and corning home very late, for me anyway. Riding Joan's, my cousin's bike, along the lane to the farm and thinking I heard the tire go down rapidly. Stopping, finding nothing wrong and turning round to find Joan had made the noise from a piece of grass between her palms. She found it very funny, but, as someone else has said, I was not amused.

I wanted to go to the market with Uncle Fred. Finally, getting a "yes" and then, the horse, the same one that I was riding and almost ran into the barn door with: refusing to move when the cart was loaded. Being encouraged to do so by Uncle Fred, the horse reared on its hind legs. I later learned it had bitten Uncle Fred. I think they finally got the horse moving, but I was not a passenger. I never saw an animal born on the farm. I had to wait until coming to Canada to see that on Greenhough's farm. I do remember being saddened at the sight of three or four young foxes Uncle Fred had shot. They had been laid on the lawn in front of the house.

One chore I do remember I had to clean out a pigsty. It had not been cleaned for years, and the manure was 2 feet deep. If you don't know what the smell of pig manure is like, don't bother to find out. My relationship with the material was not renewed until we came to Canada. Canadian pig manure is as pungent as British. During the summer swallows and martins (one or the other or both) were found in large numbers around the farmyard. Some nested in the cow barn. I climbed the rafters and looked inside and was (quickly) struck by the fact that the birds, with their mouths wide open, looked like snakes! I did not linger for a second look.

Uncle Fred (according to him) was a crack shot with his double-barrelled gun. I only went hunting with him once. I was probably too young before. He saw, and quickly and fired at a rabbit. The rabbit rolled over and over and just kept a running. I kind of remember that Uncle Fred was not too pleased. However, he did not swear. I don't remember ever hearing adults swear around children, or children swearing!! I remember seeing Uncle Fred being dragged along behind a calf that he had roped and was trying to pull the calf in the opposite direction to the one the calf had in mind. I could not believe that an animal that small, was that strong, but believe you me they are, even a few hours after birth.

I received my first taste of Army discipline down on the farm. Jim, Joan's husband, Uncle Fred's and Aunt Lizzie's daughter, was a member of the Black Watch, a very famous Scottish regiment. He made me clean my one pair of shoes several times before he was satisfied. As I recall it was the last day of my holidays. Just the day before, I had set a snare for a rabbit. Of course, the snare was set out in a field and my shoes got very muddy when I went to check the snare. No, I didn't catch a rabbit. I do remember, that I clean my shoes and that I had to clean the welts; the portion of the shoe between the uppers and the sole. Strange man. Some 10 years later, when I was in the army, the lesson learned came back!

Do you know what ferrets are? At one time in Edmonton they were all the rage as pets. That was in 1989-90. Anyway, they are quite small, about 15 inches long from head to tail, and look like rats. Are you any the wiser? Uncle Fred kept a couple in the stable. They were used for catching rabbits (sorry for the rabbit stories, Trish and Sarah! !). They were taken to the warren, a place where rabbits live, naturally. Not in apartments (ha). One or perhaps several of the exits from the warren were covered with sacks and nets, the ferrets were sent down the burrows to 'ferret' out the rabbits: Hence the term 'ferreting out'. Then, I suppose, the rabbits were used for things such as stew. Lovely. These animals, the ferrets, not the rabbits, were considered to be ferocious and I was constantly warned not to put my fingers in the cage in which they were kept. That is why I could not understand why people would want them for pets. They are not pretty looking creatures either.

I remember (must have been a bloodthirsty kind of guy!!) being involved in the massacre of thousands (well dozens) of field mice. These always (apparently) congregated in the base of haystacks. On this particular day the last remains of the haystack was removed revealing the little monsters. We then thoroughly enjoyed ourselves by beating the poor little animals to death with sticks.

On occasion Uncle Fred must have hired extra people to work on the farm. I remember hearing them discussing that one should use short handled hoe as opposed to standing up with a long handled hoe. Heavy stuff this, but the answer was, use a short handled hoe. Stay down for as long as you could, getting up as infrequently as possible, and you would not get a backache. There now you have the secret to sell, if people still hoe.

Uncle Fred and his son Ernie always seemed to wear long sleeved shirts, even on the hottest days of summer. When questioned, the amazing response was, "What keeps out the cold, keeps out the heat". Remember where you first heard this!!! One point of interest and I'm sure a source of amusement to over washed/showered Canadians. I don't recall ever having a bath on the farm. I only recall brief encounters with bowls of water. There were no underarm deodorants in those days for the common folk, either.

I have very few memories of Auntie Liz except she always seemed to wear a smock and a summer hat. I don't recall being disciplined while down on the farm. This will confirm what you have been told many times, I always was perfect. I think Auntie Liz was 'chapel'. This meant she was anything but Church of England. It probably meant she was a little more serious about her religion. I did not notice anything different. All the family were just decent people.

Listening to Uncle Fred, one learned that he was probably the world's greatest fast bowler (cricket). I remember my dad telling me Uncle Fred was very fast but terribly inaccurate: Probably why he was still farming.

He taught me one very forgettable verse: John, John, the hens have gone, The cock don't crow no more You went to bed, you sleepy head And forgot to lock the door.

I remember he played the accordion (three cheers for the accordion!). He played fairly well, and sang. He was closer to Willy Nelson than Pavarotti. Perhaps God erases bad memories, because I only have good memories about the farm. The people all seemed friendly and very kind. The life style was relaxed, even though the war was going on. I saw Uncle Fred for the last time in 1971. You kids were in the car. He remembered me, and that was after over a 25 year gap!! Uncle Fred and Auntie Liz had three children. You wouldn't have known or seen any of them. They all seemed a pretty fair bunch. There was one incident you might get a chuckle out of. I was a pageboy at Joan's (one of the children) Wedding. I was about 5 years old, wore a pink silk suit, at least it started out pink, but was a definite black at the end of the evening.

All in all, I would not have missed being down on the farm. 1A great grandson of Auntie Liz contacted me about the farm. He asked if I had any memories. I sent this article and then learned there was not a thatched roof! 21999: I read somewhere that England was sending thatchers to Japan...the Japanese needed help THE ARMY ARMY In the fifties (1950's that is) every young man in England, was required to spend 18 months in the armed forces: The exception being if he were still in school or an apprentice, or was in a special job. This meant joining either the Army or the Air Force. The Navy was fussier and would not take men on National Service, the name given the period of service. This presented no real problems for me, apart from natural apprehension; it was just another phase of life that one had to go through. That sounds really corny, but people never seemed to make such a fuss of the 'phases of life' or whatever, as they do now. We never had the time to discover ourselves. Back in the old days, you were born, went to school, went to work, did your time, (National Service!) got married, retired and then died. Life was less complicated.

Shortly before my eighteenth birthday I received my call up papers telling me I had to go to an office in Southampton. I'm not sure which came first, but there was a Medical and an interview with a sergeant. Because of the interview, I decided to join the Grenadier Guards. I signed on for 22 years, with the option to leave as each third year occurred. So, at 18, I had a career. The medical came next, lines of young men standing around in their birthday suits, coughing in all the right places. The result was, I passed the medical with 'flying colours', fit to serve in the furthest flung comers of the Empire, doncha know!" The doctor found, and marked on my medical that he found fleabites on my shoulders. Mum, no she didn't come with me for the medical (!); however, she was horrified when I told her. You have to know that having fleas was a sign of un -cleanliness and gave all those bad impressions Mum was so worried about. The doctor found no fleas. It would not have been surprising if he had as I worked on a market garden where there were animals. All the animals were carriers of fleas.

It seems that after the medical and the actual 'signing on' there was a delay before I got my marching orders. Eventually the orders arrived and I was to report to the Guards Training Depot, Caterham, Surrey. While for you guys a 100-mile trip is peanuts, to me, it was my first real journey away from home. Further, I had no idea how to get to the place. It meant changing trains a couple of times, culminating in a bus ride. I distinctly recall receiving many looks of sympathy when I asked for Caterham Barracks, the Training Depot for guardsmen. I should depart from this discourse at this point to tell you something about the Grenadier Guards. It was, and still is, recognized world wide, as a fine regiment. The training is one of the toughest in the world. They say, and it is true, once a Grenadier ALWAYS a Grenadier. The Regiment was formed in 1656, and since then has won many battle honours and awards. Don't let the Americans convince you they did it all. They just blow their trumpets louder. The Regiment, along with others of the Household Brigade are, during peacetime, responsible for Guard duty at many of the tourist attractions in London. This includes Buckingham Palace, Tower of London, St. James' Palace, and I believe, still, at night, the Bank of England. In wartime they are usually shipped to the trouble spots. They have served more recently in the Suez, Northern Ireland, Falkland Islands and the Gulf.

Now back to my story: On arrival at the gate I approached a sergeant, (this much I knew about the army) he was a fellow from good old Totton. He chose not to recognize me. I quickly learned that trainee guardsmen did not really exist, except to be shouted at and 'driven', not in a vehicle, I can assure you, but by everyone else who took it into their minds to. He managed to give the impression that he was looking down at me, even though he was only about 5'11 ". He shouted, "Piquet" and a body, dressed in uniform, appeared from what I later was to learn was, the guardroom. He obviously knew where to go. I was given instructions to follow him so took off after him, travelling at a pace I was not yet used to, though I was never a slouch.

I forget much about the first several days. There was a long episode of filling in forms and generally being yelled at. Utter confusion. At some point in time there was an aptitude test. I remained a guardsman, so obviously I had made the right choice. Ah, well, that's life. A hair cut, one of many I was to endure in the next several weeks, was fitted in somewhere in the hurly-burly, It seems to me there were five barbers, same number of chairs, and twenty-five or so of us. Fifteen minutes later all of our hair had been cut. Real punk, but no safety pins. I remember one lad crying as they cut off his wavy hair. What was under the hat was yours, what was outside was the army's. The barbers assumed our hats would just sit on the tops of our heads.

We were billeted in a large hut for about three days, while they, the Army, we later learned, was securing enough 'victims' to form a squad. I always remember my Mum telling me that guardsmen were gentlemen's sons. This illusion was shattered at the first meal. It was absolute bedlam, survival of the fittest. If you sat in the wrong spot on the table you didn't get any bread. You quickly learned! What I discovered later was that it was the officers who were the gentlemen's sons! Needless to say they didn't eat with the unwashed. The life of leisure did not last long. We were assigned to a squad, and a barrack room that would be our home until we graduated from the Depot. There were about 20 of us. Some were regulars like me; others were common National Servicemen whom we looked on with some unwarranted disdain. We were all in the some boat and we would sink and/or swim together. Most of us were 18 to 19 years old, although a couple were quite ancient at 26 years of age: Mostly from a working class background. If I only tell you half of the things we went through you will all wonder why we put up with it. Quite simply, we were prisoners of the system. Literally, whom would you complain to? All people at the Depot, apart from your group, were part of the system: a system that had been in place for probably a hundred years. It was a system, which worked to mould green (light and dark!!) recruits into a cohesive, military unit. It worked before, it worked then, and it still works now.

In spite of the dumb things we had to do and had done to us, there actually did come a day in the life of the squad when you knew you had arrived. At that point everything fell into place, and junior squads accepted you as a guardsman and; although you had not yet completed the training. The instructors knew that you had made it, because they had helped you arrive and they felt some pride in a job well done. It arrived in week 8 of the 12-week training period. There was not too much room for individualism, though you were expected to be self-reliant. You ate, slept and drank as a squad. You suffered as a squad, you rejoiced as squad. (Sounds like church ... but I can assure you that was where the similarity ended) You learned very quickly you had to stick together. Those who didn't fit in were removed, sounds terrible, but one day they were there, the next day they had left. We had one fellow try suicide, not very successfully; they found him standing in front of a mirror, dragging his razor across his throat. It was enough to get him transferred to another unit. Another was transferred because he never did learn his left foot from his right. He appeared to have been a card short of a deck. I think he was sent, 'in disgrace', to learn to drive a truck. In retrospect, we marched everywhere, he would have driven. I'm not sure who was the craziest. I mentioned, we were now in our assigned barrack room. The room was one of several in trained soldier was, was a trained guardsman, but he certainly could have been the Deity or someone from a warmer clime. He, however, controlled our destiny, night and day, for the next 12 weeks. You did not even move without asking him. He was the original! !@$#%&! He was well over 6'4", probably 220 lbs plus, and, as Jim Crouche would have said, "meaner than a junk yard dog" (and then some). In another country he would have qualified for the Gestapo. Or at least we thought he could and probably was, only with an English accent. If you don't believe me, take a look at him in the photo, he's DANCER, and I can assure you, no Fred Astaire. Looking back almost 40 years later, it is easier to appreciate his position, and to understand to some extent, his attitude. He was responsible for teaching us recruits to survive. He taught us how to spit and polish boots (officially the polish was forced into the boots to fill in the cracks and pimples, and solidified with spittle) but everyone knew the leather was smoothed down with a hot iron or spoon, and then shoe polish was added in quantity to the smooth surface along with the essential ingredient, spit. This, with the addition of elbow grease, lightly applied, did indeed, create a sparkling surface. It was mandatory that you could see your face in the shine. He was responsible for us learning all the strange things associated with barrack room behaviour: How to layout a kit inspection (all the equipment, clothes issued by the army). And, they did issue everything, right down to dark green under drawers, possibly stolen from the French at the Battle of Waterloo! He taught us how to layout lockers for inspection, how to make up your bed. If we screwed up too badly, he got the blame.

Let me quickly list some of the things we did. If you wanted to leave the room you had to go to the door, bang your feet in a drill movement, and say, " Leave to fall out, (i.e. leave the room), Trained soldier." Simple enough, however, if Dancer was in a bad mood you might have to do this several times, before he would even acknowledge your presence. You could then get remarks like, "are your feet sore, I can't hear you?", indicating you had not stamped your feet loud enough; or, sometimes a straight 'NO'. The next poor slob would do it exactly right, based on Dancer's with Battle honours remarks about apparent lack of sound, only to be told "I'm not @#%& deaf, try it again". If you had running shoes (plimsolls) on, your movement was not loud enough, if you were wearing boots, too loud. You had to go through this rigmarole every time you left or entered the room. He 'shared' in your food parcels, and let me tell you, two things were evident in your life. You were always tired, and always hungry. Not necessarily because you were underfed, or did not get the required amount of sleep, but you were always on the go during the day. You were always moving at a very quick rate of speed, arms swinging, and, as they constantly yelled at you, "dig your heels in". He 'allowed' one of the fellows go to the canteen to get snacks, if we collected enough to give him some. He was a brutal person, it was not unusual for him to strike recruits if they flubbed up on some small thing they were required to do. There was no recourse; you couldn't even show a retaliatory response. Or at least we didn't; having said that, I really don't bear him any grudges. I didn't like his style, but he was respected throughout the Depot, as one of the best. This was of course, not based on how he got the good results he did, but on the good results.

Let me run (and sometimes we did) through a day. Wake up was at 6.30 a.m. but we were always up long before that. There was washing and shaving, always with cold water, to be done. The cold water was not punishment; I really think the place was so old there just was not any hot water. The only time we experienced actual hot water was in the weekly shower. That in itself was an unforgettable experience. The words of command were, "Get undressed, get in the shower, get out of the shower" Expletives all deleted. And it seemed like the amount of time allowed was about as much as it has taken me to type this portion, i.e. the words of command!! Why up so early you say, there would not have been enough time to do what we had to do before we were scheduled to go on parade!! First a fair hike to breakfast and back: The last minute cleaning of boots, badges and belts, and, for heavens sake, the setting up of the room. The room had to be set up just so. Let me explain, if I can remember. By now, the equipment in the form of belt, ammunition pouches, haversack and backpack had all been issued. It had to be blancoed, blanco was a green substance applied wet to the outside of the equipment, which presumably preserved it, but was also camouflage. The equipment, minus the belt, had to be squared off with cardboard and had to be set out just so above your bed. Each piece had several brass attachments. The brass had to be cleaned everyday. Somewhere on the large haversack you hung your nameplate1, made of brass and had to be shined everyday. Along side of the bed was a locker; this was left open during the day for inspection. Every item in the locker was on display. Knife, fork and spoon, eating for the purpose of, mug, enamel, drinking, for the purpose of: A housewife, which was not a French maid, but a small satchel in which was a needle and thread, wool, and thimble. And one of those wooden toadstools you put in a sock when you dam it. In the bottom portion were your best boots, shined. To one side was your rifle, somewhere else your great coat, properly folded and all the buttons shined.

Every morning beds had to be made as follows: The mattress was folded in half, and the crease side placed at the end of the bed. One blanket was folded to be a wrap around. The sheets and other blankets were folded and then, wrapped around with the first blanket you had set aside. The sheets and blankets were in order so you finished up with a product looking like a layered cake. Again, everything was supposed to be square and straight, and, well you get the picture. I know you are probably saying what was the point? Think about it. It was one way of ensuring the beds were aired, and perhaps, discovering those that may have need medical attention for problems that had not come to light earlier. Then, and I don't believe this myself; the beds on either side of the room were lined up in two rows. They remained in the same location, but the ends of the beds were actually lined up by stretching a piece of string from one end of the room to the other. Each pile of blankets was also lined up. Beside your bed was a kit bag, which if you were moving anywhere would be full of clothes. It was about 9" in diameter and 3' long. The material was quite stiff, which was just as well, because you had to stand the kit bag up, empty, and line them all up. Then the handle, which was of rope had to be twisted to stand up, straight! The dumb part about this whole exercise was that in time you actually enjoyed doing it, and, in effect, in your own mind, defeating the system by doing these ridiculous things, well. However, in actuality losing, because not only were you doing what the system wanted, but you were actually enjoying it!!

Then, of course, there was the floor, made of hardwood, which had to be shined every day. You had your own bed space to do, plus a portion of the floor. The floor was shined with steel wool, and buffed with a blanket. It required the cooperation of everybody, the "skivers"2, those who sluffed off, were quickly determined and they were made to do their share. All the responsibility for teaching us these earth-shaking duties fell on the Trained Soldier's shoulders, and large as they were, it sometimes, I think, laid heavily. The Trained Soldier survived 13 weeks with us. I don't suppose he was any more pleased to see us leave than we were to leave him.

The first sergeant we had was a 'gentleman', and I suppose, based on the results of our first pass out inspection, four weeks later, was returned to the battalion. We undoubtedly took advantage of him, although, unbeknownst to us, it was to our detriment. You have to understand that a Trained Soldier, although actually only a guardsman, was, at the Depot, a person of authority. As recruits we had to stand to attention when we spoke to him. A (lance) corporal, wearing two stripes was even higher, and the (lance) sergeant, who had three stripes, was thought to be able to walk on water. Let me insert a little of Brigade of Guards history here. In all other army units within the British Commonwealth a lance corporal wore one stripe, as did lance corporals in the Brigade of Guards, way back, even before my time. Apparently Queen Victoria saw a guards (man) being posted, not mailed, but taking his position at his post. This was not a wooden stake, but the position he would remain at for the next two hours, by a lance corporal, with one stripe. She was not amused by the one stripe he wore to signify his position, and ordered that in the Brigade of Guards; lance corporals were to wear two stripes, Corporals three. Next there was a colour sergeant, who wore three stripes and a crown and so on and so on. Those of higher rank, very seldom acknowledged our existence, unless it was to administer some kind of discipline. Where was I, what has the above to do LlSgt. Bunny Whitehead with the downfall of the sergeant. Basically it was because he found it hard to accept the required, strict separation between recruits and non commissioned officers. He would visit the barrack room in the evening and chat with us. Somehow we must have picked up that he was not tough enough. Consequently we did not learn our drill procedures as we should have done. We flunked our fourth week inspection. Had we passed we would have been entitled to our first weekend pass. Quite a disappointment: In addition, the sergeant was returned to the battalion, in disgrace. We were to pay the piper for the sergeant's downfall.

The next sergeant we had, and I might add the last one, was a sergeant Whitehead. Dancer, in comparison, was a wimp. Whitehead was only about 6'3", not as heavy as Dancer, but mean, again, look at his picture. You will know the meaning of esprit de corps. This came into play as soon as Whitehead took over. It appeared that everyone who had any authority of any kind was going to get in the blows against this squad that had done so miserably, and had their sergeant back in disgrace to his battalion. The fact that basically it was his fault had no bearing on the issue at all As the expression went, our feet never touched the ground for the next several weeks. We certainly paid the price for the sergeant failing, as it implied he couldn't cut the mustard with a training squad. By never allowing our feet to touch the groundmeant that we were doubled everywhere, continually yelled at. Any free time was cut to a minimum. Any sign of slacking off meant an immediate journey to the drill sheds where we were (illegally) marched to the beat of a drum, and let me tell you that could be very fast.

Each morning started with a drill parade, but more about that later. You would have dinner, it was a little more relaxed after lunch; at least you could stay on your beds now that the room had been inspected. We made extraordinary use of our beds; they were our beds, tables and chairs. There was no other furniture in the room apart from the beds and lockers, and a table for ironing uniforms on which we were not supposed to do, and didn't incidentally, the Trained Soldier did though. The mid morning parade, gave those who had the privilege of doing it, time to inspect the barrack rooms. By the way, we were in a barrack block that housed several squads of men. One quickly determined whether the room had passed inspection. If the room was not up to standard, you could expect to find your bedding in a heap on the floor. Contents of lockers thrown all over and boots dumped in the water in the fire buckets. Like I said, it was quite the system, but who was to argue? More military stuff in the afternoon. In the evenings a jolly time was had by all. It was equipment-cleaning time. And of course, equipment was never clean/shiny enough for Dancer. It could cause you, if you didn't reach the required standard to spend time in the washroom, after lights out, which was also illegal. Checks by senior sergeants did not occur often, probably just often enough to say checks were made on a regular basis to fulfill some regulation ensuring soldiers were not required to stay up beyond lights out without good cause. I doubt if any member of the squad failed at one time or another to bum the midnight oil in the washroom. Needless to say your instructions, which you had to deny you had received, were to say that you just wanted to look better and that you chose to spent time in the washroom. Back to the equipment cleaning: You used your bed as a bench, except for any water assisted cleaning of the belt and pouches. You sat for a fixed period of time. Ninety minutes comes to mind, straddling the bed, with suspenders down. Goodness knows Why. While cleaning, you were expected to listen to, and become familiar with, the bugle calls that were sent across the Public Address system. There is a bugle call for everything in the army. Well almost everything. The bugle calls, played by a drummer, included calls to get up, go to bed, pay parade, alarms, ad nauseam. In addition we were expected to learn and remember all the battle honours of the regiment. There were around fifty when I was in. The sergeant would occasionally visit, and normally, at least with Whitehead, they were not social calls until we were well on our way to graduating. Again, no trips to the canteen, except for one person, who took a long list for the squad, and one for the Trained soldier, who had to be fed.

At ten o'clock, 22.00 hours, the cry "Stand by your Beds" was heard and you had to stand on the end of your bed, pants rolled up to the knees, suspenders dangling. The picket, occasionally spelled piquet, sergeant who was the duty non commissioned officer for the period, arrived shortly thereafter and determined that everyone was in, there was really nowhere to go, unless you were sick, or absent without leave Generally speaking, at this time of night they were much more human, and would joke around a bit, just to let you know there was an end to the training. As you progressed in your training so the strict regulations were relaxed, just a little. Please don't the impression it was terrible all the time. What the training did was to get you to share with others, and develop a philosophy covered, in Canada, by the letters, d I t b g y d!5 You have to remember that it was the squad that graduated, not a group of individuals. It meant that those who picked up the system quickly helped others. Of course, some of the methods would make your hair (I had some then) stand on end. Depending on the circumstances, help was either pleasant or unpleasant. If it came to cleaning equipment those that could do it better helped out the others. The Trained Soldier helped as well. Remember you graduated as a squad, so it required all the squad to pass the inspection.

However, there was the Obstacle Course. This would be a layout in a field with walls and barriers and water and things like that. Every squad had one or two men that couldn't swing like Tarzan and would let go of the rope too soon and fall in the very slimy water. Or, unable to climb the wall or jump down from a six foot log fence. This, in the view of the system and the other squad members, showed any individual weakness that had to be corrected. It could mean the difference between survival and whatever, and it had to be an individual effort. Those who could were always able to complete the course sat down and waited for the inevitable. Not recommended these 'politically correct' days and it didn't really help in those days either.

You shared food parcels with the fellow next to you and with the Trained Soldier if he heard the rattle of paper after lights out. Our Trained Soldier, in retrospect was not very smart, he had one of the guys write his letters to his girl friend, but he did try. He would take the odd weekend off. He would broach the subject by saying .. "I have the opportunity to go home for the weekend but I'm broke, if have to stay here then your lives will be as miserable as all get out", that was the general drift of the message. A passing around of a hat always resulted in enough 'gifts'. Soliciting funds would have been illegal. We didn't begrudge it and we only received a pittance for a salary. I remember on one occasion he explained he was going out to tie one on, get drunk, we decided we would get a measure of revenge. I don't recall it as being malicious in any way; after all, Dancer had most of the answers to the questions for us to get out of the Depot. We simply made an obstacle course from the door to his bed, which was in the far comer of the room, with kit bags. He made the bed, with some difficulty, and took it all in good sport.

As I said earlier we failed our first pass out parade, miserably, and everyone seemed to know about it, the instructors, the other squads. You really suffered. However, after a week of Whitehead we tried again and made it. All seemed to be forgiven. We had now been prisoners of the system for almost six weeks. We were anxious to get home. The system, however, had not done with us. We got dressed and as a squad were marched to the guardroom to be inspected to see if we were good enough to get out of the barracks. It was about a mile, or so it still seems, to the guardroom. We were marched to the guardroom, almost, turned around and marched back again almost to the barrack block. I swear we did this at least 6 times. Finally we were stopped at the guardroom and inspected by the sergeant who sent everyone of us back to the barrack room because our shoes were dusty. I kid you not, I know, I hear you all saying they wouldn't do that to me ... wanna bet!!!

While I remember, a couple of things stand out in my memory, the first, shortly after we were settled in as a squad, the question was posed, "how many of you are confirmed" (in the Church of England). Those that were not were sent on the appropriate course and in time were confirmed. I had been. It had nothing to do with Christianity. It was just something that they army was 'concerned' about. The second of the things was not really related but when you had time to think, which was infrequently, you knew just how hungry you were and just how tired you were. You ate anything and everything you could lay your hands on. Army food, as I recall, was barely one step above pig swill, and the cooks, who must have shuddered if they had actually been taught to prepare meals, seemed to ruin everything they tried. I have eaten roast, boiled, and stewed corned beef. If BBQ's had been available we would have had that as well. As for the tiredness, if you received class instruction you were always in danger of falling asleep. And it was dangerous, if you were caught, you finished up in the clink.

You learned several Grenadier traditions, which will mean absolutely nothing to you but which I am going to tell you about anyway. Everyday at 16:30 hr., and usually as you made your made your way to eat; the drummer (bugler) would sound 'retreat'. Now, Grenadiers do not know the word retreat, so, while everyone else around you marched on, you stood still. You never said, "Yes" either, goodness only knows why, so if the Sgt said, Tidridge you are a dumb cluck, right? It would be wise to answer, smartly and sharply, "Sergeant": Which was always pronounced as Saaarntrt!!!! (It was never wise to argue with a sergeant). Just one more and then I am finished. In drilling with a rifle there were several orders that included the word Arms i.e. rifle, however, Grenadiers did not say the word, "arms", so it was anything, more or less, that followed the direction, such as slope .....

The physical training was fairly intense, not very imaginative. There was no slacking off but at least most fellows could run and jump and keep in time with the fellows in front. If you couldn't you could always hang on the wall bars until you thought you could. I think the 'drills' they did were dreamed up long before my time and I doubt very much if they have changed. When I joined the Police Service we did the same kind of things. I thoroughly enjoyed physical training, PT as we used to call it. You might think: that as we were going to PT we would change completely ready for it. However, that was not the case; you were in vests, shorts, socks and regular marching boots. Your running shoes were wrapped up inside of your towel. If it rained or was cold you wore the same stuff, but wore a greatcoat as well.